Paolo Aversa, City, University of London

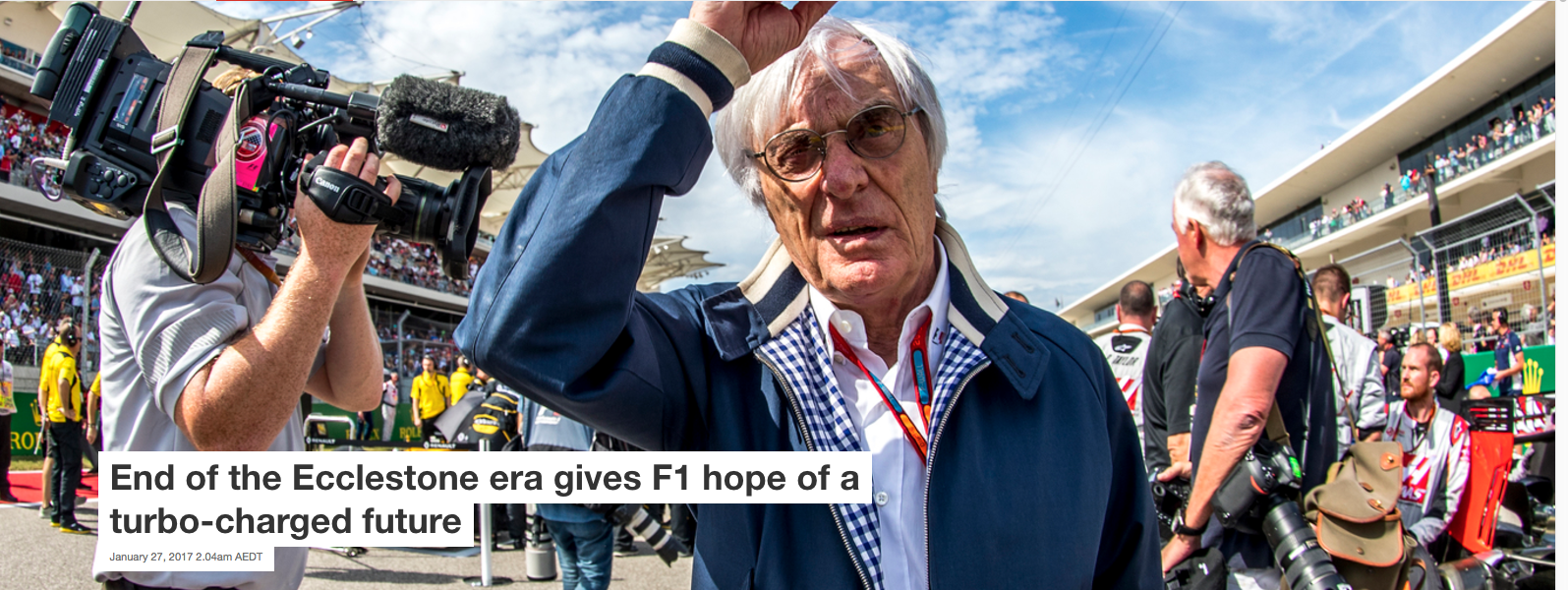

Bernie Ecclestone’s removal from the head of Formula 1 is almost hard to believe. Despite a rollercoaster life, a costly bribery trial, and a triple coronary bypass, the 86-year-old F1 supremo has never showed any sign of relinquishing his dominion over the sport.

It is, after all, an industry that he created and transformed from a grassroots racing hobby for a few adrenaline junky mechanics, into the most-watched sport series in the world. So, as US giant Liberty Media takes over F1’s parent company Delta Topco, the decision not to keep Ecclestone as CEO marks a major change to F1’s business model.

From the ground up

Ecclestone has often made the news for the wrong reasons (questionable commercial strategies) , allegations of bribery, a colourful array of politically incorrect statements which included praising Adolf Hitler for “getting things done”). But loved or loathed, nobody denies his critical role in building Formula 1 over the last 40 years.

Having started his career as a second-hand car and motorcycle salesman, Ecclestone began racing as an amateur driver in 1949. After some stints managing drivers, he became the owner of a small Australian team, Brabham, in 1972. This was instrumental in transforming his own fortunes and that of the sport.

Back in the 70s, the business of F1 was made up of an unstructured, unfair and inefficient system of one-to-one deals. Each team would independently negotiate with the track owners a fee for their participation in races. This granted higher bargaining power (and richer deals) to prestigious teams, which were considered a “must-have” to attract spectators. Smaller ones got next to nothing. At the same time, the track owners would sell broadcasting rights to TV and radio channels on a race-by-race basis.

Joost Evers, CC BY-SA

Ecclestone was the first to realise this system was unsustainable and advanced a solution. In 1978 he become the president of the Formula One Constructors’ Association, the F1 teams body, and offered to represent all teams’ interests in a centralized system of negotiation. This granted returns to all parties (including the smaller teams) and higher profits across the board from the direct negotiation with broadcasters.

This central arrangement transformed F1 into the extremely profitable industry it is today. Audiences – and sponsorship – skyrocketed around the globe.

Ecclestone’s ability to make money seems to be second to none. He brought races to locations such as Bahrain, Russia and Azerbaijan where national governments were willing to pay multi-million fees. At the same time all TV rights were progressively sold to pay-tv channels through costly multi-year contracts. Revenue for the ten teams competing in F1 in 2015 was US$1.5 billion.

Hit some road bumps

The sport has, in recent years, however, witnessed a dramatic plunge in its audience and overall traction. Excessive regulation has limited the development of car technology, prohibiting the appeal of races. A small number of teams dominate and the result of races is often predictable. Ticket prices are so high that only the very wealthy (or die-hard fans) can afford to watch the sport live.

Ecclestone’s tight grip on the sport is a big reason it hasn’t evolved. Despite dwindling audiences, he preferred to perpetuate the idea of F1 as a glittering world of golden gates and VIP passes, where ordinary fans are kept at a distance from their heroes and the show is conceived to target older, deep-pocketed, nostalgic motor-heads.

Necessary reinvestment was reduced to the very minimum. For example any sort of significant engagement with the internet and social media were dismissed and were instead promptly and successfully adopted by Formula E, F1’s sister series.

The complacence of teams in this was bought by establishing a governance system where top teams (namely Ferrari, Mercedes and Red Bull) have higher powers. They can basically veto any changes to the sport that do not work in their interest. This includes proposals like a cost cap for technology, or a more fair redistribution of revenues to help minor teams “stay in the game” – and make the sport more competitive.

It did not take long for Liberty Media to realise that the way Ecclestone set the business up is not geared towards making any radical changes. The decision to appoint a new managing team and dismiss him with a pompous but token title of “chairman emeritus” shows a desire to take the sport in a new direction.

Turbo boost

So those hopeful of a rejuvenation of the sport have welcomed the news. The sport’s new chairman, Chase Carey, a former 21st Century Fox executive, has said that Formula 1 will be run differently.

Top priorities will be expanding into the US (while maintaining its presence in Europe), and greater effort will be made to engage younger generations. Carey has talked of introducing “21 Super Bowls” to the F1 race calendar. Inspired by the American sport series format (familiar to American football and baseball fans), it will be a more engaging show for fans to follow. It’s a promising recipe.

Crucially, Carey will have a strong new team around him. The experienced Ross Brawn returns to the sport as managing director, to lead the technical and sporting side of things. As former Mercedes team boss and technical director of Ferrari, overseeing Michael Schumacher’s seven world titles, he is one of the sport’s best. His task will be changing race regulations to bring back exciting races that can be enjoyed by even occasional viewers. To bring in the revenue, he is joined by ESPN veteran Sean Bratches as commercial managing director, focusing on sponsorship and broadcasting deals.

Having been in the hands of Ecclestone for so long, this new trio will have a tough job of implementing the revolution that fans have been longing for. Still, a study I recently conducted with colleagues Simone Santoni, Luiz Mesquita and Alessandro Marino shows that this change to F1’s management bodes well. Our research found that when top management teams in F1 are made up of members with more diverse background and experiences, they will be more effective and efficient in embracing innovative solutions and making bolder decisions.

If this is the case, Liberty Media’s F1 takeover might not be the sport’s last lap, but perhaps just a useful turbo boost to revamp the industry.

![]()

Paolo Aversa, Lecturer in Strategy, Cass Business School, City, University of London

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.